Value Based Care: Why we need it and how to get there

Dr Phillip Matley describes how collaboratively we can lead the transition towards improving value for patients which means improving the outcomes that matter to patients.

Doctors in South Africa love the fee-for-service system they have grown up with in spite of the fact that it emphasises volume rather than value. There is little doubt that it increases utilisation, encourages over servicing, provides no incentive to reduce costs (or even be aware of them), fosters fragmented care with duplication, and fails to reward quality or efficiency of care delivery. Perversely, it often rewards bad performance (a readmission or reoperation generates further fees). Audit and quality measures become largely irrelevant. Fee-for-service is contributing to the rising costs of healthcare which everybody agrees is currently unsustainable. There are powerful forces directing a change towards value based care.

Value in medicine is obtaining the best clinical outcomes and patient experience (quality) at the lowest cost (both direct and indirect). To maximise value for patients, we have to move from a supply-driven health system orientated around what doctors do, to a needs-driven health system orientated around what patients need. The former emphasises volumes, profitability, visits, admissions, procedures and tests, whereas the latter is focused on the patient orientated outcomes that are achieved.

The move to value based care has been championed by some notable individuals (notably Michael Porter at Harvard Business School) and institutions such as the Cleveland Clinic and the Schon Klinik but the question is "Who will lead this move in South Africa?". The lead is currently being taken by organisations such as Discovery Health Medical Scheme, Medscheme and PPO Serve but it is doctors who really should be taking the lead. Value is determined by how medicine is practiced and we are the ones who know this best. The transformation must come from within the profession. Only doctors and provider organisations can put in place the set of independent steps needed to really improve value, but everyone has a role to play, including hospitals and patients.

The goal has to be improving value for patients which means improving the outcomes (without increasing the costs). Value-based care is not at odds with profitability. Groups that provide value care will see their volumes increase, and they will enter contracting negotiations from a position of strength.

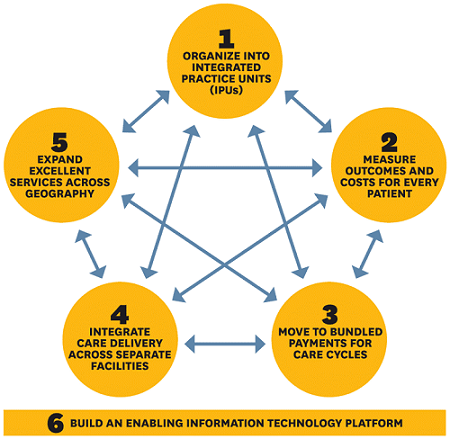

In his seminal 2013 Harvard Business Review article: "The Strategy Will Fix Health Care", Michael Porter described the Value Agenda, a six-point plan:

1. Organise into Integrated Practice Units (IPUs)

IPUs are organised around a condition or set of related conditions with care provided by multidisciplinary teams in dedicated facilities. The care is overseen by a lead clinician and the team regularly meets and uniformly measures outcomes and costs for every patient. IPUs provide faster, more effective treatment with better coordinated care, better patient outcomes, lower cost and ultimately increased market share. Compare the haphazard process whereby a patient with back pain will have this problem addressed in South Africa today with the Spine IPU at Virginia Mason Hospital in Seattle that provides patients with a same day assessment by both a physical medicine specialist and a physiotherapist to triage patients into those with immediately dangerous conditions, those likely to need surgery and those likely to respond to physical therapy which begins immediately. They have demonstrated a significant reduction in time off work and the number of physio visits, a huge reduction in unnecessary MRI scans, lower overall costs and increased patient volumes.

2. Measure outcomes and costs for every patient

Rigorous measurement of value is the single most important step to improving the quality of healthcare and whenever this is done, quality improves. Studying outcomes and benchmarking themselves against their peers motivates surgeons to work together with their colleagues to improve outcomes. However, it is vital to measure what is important to the patient. Measuring HbA1c and LDL may be helpful in diabetes, but patients want to know the impact on their life expectancy, loss of vision, amputation rates and risk of heart attack and stroke. Recently, a hospital in the Netherlands received a national award for excellence in diabetes care but was subsequently shown to have one of the highest amputation rates in the country. Clearly, they are measuring the wrong things. Mortality rates and five-year survival may be important for radical prostatectomy, but it is incontinence, erectile dysfunction, return to work, and anxiety levels that are the patient's chief concerns. Carefully measuring these outcomes has been the key to the successful growth of the Martini Klink in Hamburg, which has become one of the busiest centres for prostate cancer surgery in the world. The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) is currently drawing up data sets for most of the global disease burden and thus far has published 23 of these, enabling doctors to measure what is most important to patients. Measuring cost is not the same as measuring charges (adding up what the specialist bills for his service is not the same as what it costs the organisation to provide his input). The important thing is to measure these costs and feed the information back to the clinician so that he can understand which activities and services can be reduced or eliminated, without compromising outcomes.

3. Moved to bundled payments

Bundled payments are single payments that cover all the professional costs of the team, all hospital costs, all device costs and defined post-operative care, occasionally including costs of any readmission. The payment is made either prospectively or retrospectively and incentivises providers to improve quality and reduce cost, as well as creating an alignment between payers, physicians and hospitals. These contracts need to clearly define both patient and doctor eligibility criteria, as well as providing severity risk adjustments so that surgeons are rewarded for tackling more complex cases. Providers are not responsible for unrelated care and there must be stop-loss provisions to protect them from catastrophic costs related to complications. Mandatory outcome reporting is essential and payment has to be contingent on obtaining good outcomes. Clinicians and hospitals that are able to provide quality care at reduced cost need to be rewarded with good profit. It is vital to recognise that without a clear knowledge of their outcomes, no provider will be able to succeed with bundled payment contract negotiations. There is now very good evidence (particularly from Medicaid and Medicare in the USA, and from Sweden) that these strategies are able to reduce overall costs by approximately 20%, with overall reductions in complication rates and mortality as well as improved patient satisfaction. Doctors should not feel threatened. They should view these programs as opportunities to retake control of healthcare and to engage in proactive discussions about how to improve these models. It only makes sense that those who prescribe care, and therefore drive both costs and savings, should lead the inevitable transition from volume to value.

4. Integrate care delivery across separate facilities

Volume needs to be concentrated in centres of excellence, but it is important to choose the right location for each service. Day clinics or in rooms procedures may be more cost-effective than big hospitals. It is important to integrate the hospital service with community care.

5. Expand the experience across geography

Once it is all up and running, it is important to expand the formula and the experience over a wider regional and national footprint.

6. Build an enabling information technology platform

In order for all of this to work, there has to be an integrated IT system that captures the right metrics in an electronic medical record to which everyone in the team has access. The data has to be patient centred, easy to extract and analyse and able to give the clinician meaningful feedback in terms of outcome data and dashboards.

Several individual doctors and group practices, in collaboration with funders are currently poised to lead this transition from volume to value in our country. We need profession driven care processes, transparent and objective measurements, and systems to facilitate improvement for the outliers without it being seen as punitive.

Michael Porter states that organisations that can master the value agenda will be rewarded with financial success and the only kind of reputation that should matter in healthcare: excellence in outcomes and pride in the value that they deliver.

Most of these changes are coming whether doctors like it or not. It is vital that we have meaningful ownership of the process.

- Michael Porter & Thomas Lee. The Strategy that will Fix Health Care. Harvard Business Review October 2013

- Jacofsky DJ. Bone Joint Journal 2017;99-B:1280-5

Philip Matley, specialist vascular surgeon and chairperson of Surgicom

Philip Matley, specialist vascular surgeon and chairperson of Surgicom