Information wars: How Europe became the world's data police

By Sarah Gordon and Aliya Ram In London

Source: Financial Times

Vera Jourova, the EU’s justice commissioner, describes it as a “loaded gun” in the hands of regulators. [In May this year the bloc introduced the General Data Protection Regulation, which its advocates argued, would dramatically improve the care with which organisations both within the EU and elsewhere treat our personal data.]

GDPR will harmonise data protection rules across the world’s largest trading bloc, give greater rights to individuals over how their data is used, put in place significant protections for children and streamline regulators’ ability to crack down on breaches.

When the new rules were first proposed, many executives in Silicon Valley derided them as restrictive and anti-competitive. But in the wake of the scandal over the use of Facebook data by Cambridge Analytica, Europe’s approach to data privacy has started to appear much more relevant.

According to many companies and data protection authorities, GDPR could become the global norm, setting standards for behaviour not just in the EU but in countries where hitherto individuals have had few weapons to defend their rights online.

“Europe was way ahead on this,” Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s chief operating officer, admitted last month (April 2018].

Yet, cracks in the EU’s vision have appeared. Many businesses are unprepared for the new rules and several countries have failed to pass the necessary legislation to implement them nationally. Serious questions have also been raised about the ability of data protection authorities across the bloc to enforce the new rules adequately.

“Everybody [left it] until the last conceivable moment, despite the fact there was a two-year deadline,” says Harry Small, head of data protection law at Baker McKenzie. “Quite a lot of companies have not really woken up.”

Even critics acknowledge that GDPR will introduce a new rigour into the messy patchwork of rules governing how our data are treated across Europe. It requires any organisation anywhere in the world that handles the personal information of an EU citizen to be transparent about how it collects, stores and processes it.

Organisations must obtain unambiguous consent to use and retain data, keep it up to date, delete old data and — if they have a large volume of personal information, data subjects and range of items — will have to appoint a data protection officer.

Digital adults

Consumers will have the right to ask for the information companies hold about them and request that their data is deleted from business databases. The rules forbid companies from processing data on race, ethnicity, political opinions, religious beliefs, trade union membership or sexual orientation without explicit consent.

Ultimately, the impact of GDPR will depend on whether individuals decide to exercise the greater powers the rules give them. They are part of a growing worldwide push for customers to mature into “digital adults”, with both greater control over and responsibility for their own information. Proponents hope that GDPR will help individuals become both more demanding and more aware of their power.

“Data subjects are going to become increasingly aware of their rights, and they’re not going to put up with poor practices by organisations,” says Helen Dixon, Ireland’s data protection commissioner.

But she points to the fact that Facebook’s registered users have increased even while the Cambridge Analytica scandal has raged as an example of the so-called “privacy paradox”, that while people say control over their data matters to them, they have remained, by and large, casual about relinquishing it.

Multinationals to adopt GDPR globally

GDPR’s reach is already spreading well beyond the EU. According to Graham Greenleaf, a professor of law and information systems at Australia’s University of New South Wales, 120 countries globally had data protection laws in 2017, but GDPR is probably the broadest and most rigorous.

For a start, any country wanting to sign a trade deal with the EU will have to sign up to respecting GDPR, the first time the EU will formally address the issue of trade and data flows as part of its role negotiating free trade agreements on behalf of its 28 member states.

For many large multinationals, it could make sense to adopt GDPR globally both from a cost and consistency standpoint. Regulators in places such as Hong Kong have based their laws on the EU’s 1995 data protection directive, and have said they intend to update them to reflect GDPR.

Yet despite the predictions about global impact, there are big questions about how it will actually be implemented within the EU.

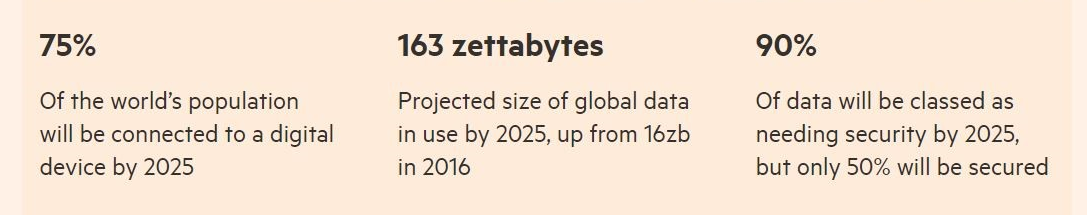

GDPR in numbers:

Source: Financial Times

Onerous and expensive compliance measures

Given the scope of the new rules, which run to more than 200 pages, preparing for GDPR has proved both onerous and expensive. Companies in the UK’s FTSE 100 are estimated to have had to spend an average of £15m each to comply with them, according to research by the legal tech firm Axiom. Meanwhile, in the US, the International Association of Privacy Professionals and EY say members of the Global 500 will spend a combined $7.8bn on compliance, an average of almost $16m each.

The survey suggests that Fortune 500 companies have each had to hire on average five full-time dedicated privacy employees — such as data protection officers — as well as another five employees to work part-time on compliance.

For some businesses, GDPR has required them to conduct an audit of what information they hold, but the task of “cleansing” databases of old or duplicate information, and contacting individuals for consents, has often taken months of staff time.

For one small headhunter in London — the sort of business where personal data about potential clients is vital — getting ready for GDPR has involved “not just a database project, but a whole programme of change”. The company has employed one staff member just to “cleanse” the data on individuals which it holds, and to contact people for consent to continue holding it.

“We used to make the assumption that because someone’s information was in the public domain, like LinkedIn or their own website, that there was no problem with us holding it,” says the person at the agency in charge of implementing the new regulations.

Given the scale of the task, a significant number of organisations will not be ready in time for May 25. A survey of nearly 200 global businesses by SAS, an analytics company, in February found that fewer than half expected to be fully compliant by deadline day.

Smaller companies across the EU and elsewhere are at particular risk. In March, the UK’s Federation of Small Businesses found that fewer than one in 10 small businesses in the UK were fully prepared for GDPR, with just under one in five unaware even of the existence of the new rules.

EU states also lagging behind

It is not just organisations which are lagging behind. In January the European Commission said that of the bloc’s 28 member states only Austria and Germany had fully adopted changes to their legislation ahead of the new regulations. While countries such as the UK are expected to pass the laws at the last minute, Baker McKenzie says five EU countries, Bulgaria, Greece, Malta, Portugal and Romania, have not even published a bill or proper information about how they will implement GDPR.

Enforcement could prove tricky

For organisations which remain in breach of the new rules, failure to comply could bear a high cost, with fines of potentially 4 per cent of global turnover or €20m, whichever is the greater. The cost of putting things right, as well as the reputational hit, could be even higher.

But there are significant question marks over whether those in charge of enforcing the new rules are up to the task.

As early as 2015 Jacob Kohnstamm, former chairman of the Netherlands’ data protection authority, was warning that organisations breaking the rules faced “little chance of being caught”. Given his organisation’s budget to do investigations, “the chance of having the regulator knock on your door is less than once every thousand years”.

The resources available to most European data protection agencies’ budgets are still a fraction of those in North America — and have only risen by about a quarter on average across the bloc in response to the increased demands on them that GDPR represents.

Giovanni Buttarelli, the EU’s European data protection officer, warned at the end of last year that the number of people working for regulators in the EU — about 2,500 — was “not many people to supervise compliance with a complex law applicable to all companies in the world targeting services at, or monitoring, people in Europe”.

Last September Elizabeth Denham, the UK’s information commissioner, said she needed more staff on better pay if the regulator was to effectively enforce GDPR. After a boost in government funding, the Information Commissioner’s Office will increase headcount by a third to about 700 by 2020, but data protection agencies and companies across the bloc are fighting to hire the trained staff they need.

“It’ll take time to build staff,” Ms Denham told the FT. “We have started more investigating . . . of social media companies and elections. I’d call that more of a proactive [investigative] culture. The whole approach needs to change.”

Ms Dixon’s office in Ireland has 100 staff and she plans to recruit 40 more this year, bringing in litigators, criminal lawyers and staff with investigative experience, for example from the insurance sector. “To use the big corrective powers that really bite we will have to be demonstrably showing we’ve followed fair process,” she says.

Grey areas

Ms Dixon is well aware of the scale of the task ahead, given that Dublin is the European home to many of the US tech groups such as Facebook, Twitter, Dropbox, LinkedIn and Airbnb.

Under GDPR one authority will take the lead on cases such as data breaches and related issues rather than the current situation where a company can face multiple legal challenges from regulators in different EU member states. In theory, GDPR prohibits “forum shopping” by companies keen to choose their preferred regulator, and objective criteria should govern who leads on specific cases.

Facebook would be the Irish DPA’s responsibility, given its central administration is in Ireland, its terms of service are associated with its Irish entity and it has a substantial data protection and privacy team in Dublin.

For companies such as Google, which provides services through its global headquarters, regulation will depend on where cases are brought in Europe. This will make it less clear which regulator has oversight over the company’s data use and privacy practices.

There are other grey areas. Advertising technology businesses that harvest data from third-party websites may have to seek consent from users. Google has attempted to deal with this by defining itself as a “controller” of data under GDPR when handling third-party information. But the designation has been resisted by publishers which will have to seek consent to share information with Google, raising concerns among their own users.

Privacy campaigners have cried foul over the imperfections of GDPR. But as the world’s attention zeroes in on data protection after revelations about Facebook’s massive data leak, officials in Brussels will hope the rules can mark a new beginning in how personal information is policed.

Control your information: Rules call for more consumer ownership

Europe’s new data privacy rules are underpinned by the basic principle that individuals — not companies — should own their personal information. For Tim Berners Lee, the British computer scientist widely credited with inventing the worldwide web, this is crucial to promoting competition on the internet, which he argues is increasingly dominated by a handful of platforms.

“We could imagine that in a better world . . . you’d have a choice of search engine and a choice of social network to join,” he told the FT. “All the photos you have on LinkedIn, Flickr and Facebook would be yours. “In a better world you’d have complete control over your information.”

The lawmakers who drafted the General Data Protection Regulation paid a visit in the summer of 2016 to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where Sir Tim is based. There they were given a short talk on his solid decentralised web project, which aims to improve privacy by building technical tools that give users ownership over their data.

The idea, which has already been implemented by some non-governmental organisations and data brokers, is a central plank of the GDPR. The rules mandate companies to allow citizens to download their data in a “commonly used and machine-readable format” that would allow them to share or sell it with other companies.

This would theoretically make it possible for a user to move between social media companies with all their information — or sell it back to the company for a price. However, Robin Jack, an independent analyst, says that most data is still unreadable. “Data is messy,” he says. “There are lots of things that are inconsistent, like date formats, whether the prices of things have currencies or not, whether times have time zones.”

Social media companies argue that the data they gather is inherently incompatible with other companies. For example the “audience” profiles created by Facebook cannot be matched with the lifestyle categories generated by Snapchat.

“It’s difficult to create that interoperability between those companies,” says Katherine Tassi, Snap’s deputy general counsel. “For example, Snap giving access to its service to another service is not necessarily meaningful.”

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2018

Source: www.ft.com/content/0d10d1c4-67dc-11e8-aee1-39f3459514fd

© 2018 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. This article has been reprinted under strict copyright agreement and purchase from the Financial Times. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.

Disclaimer

Discovery Life Investment Services Pty (Ltd): Registration number 2007/005969/07, branded as Discovery Invest, is an authorised financial services provider.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and may not necessarily represent those of Discovery Invest.